#DiscoverWithVSU: Rethinking how women are studied in phenomenological method

- Details

- Written by Mike Laurence V. Lumen

-

Published: 19 November 2025

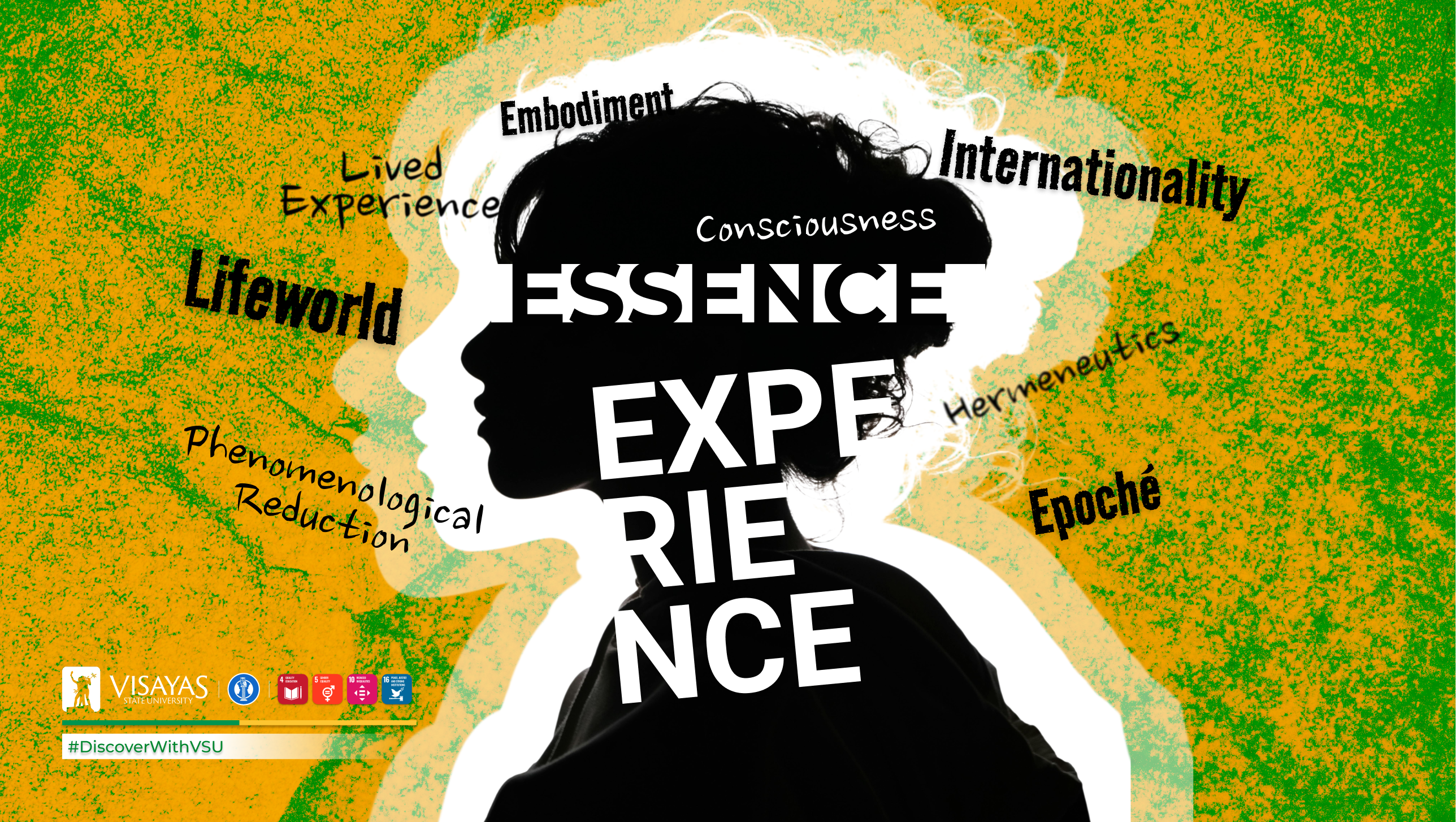

What does it mean to study the “essence” of being a woman? And does searching for such an essence truly help women, or does it end up putting them into boxes they never chose for themselves?

These are the questions raised by Mr. Beljun P. Enaya from Visayas State University-Department of Philosophy and Social Sciences (VSU-DPSS), in his paper “The Objectification of Woman in the Phenomenological Study,” published in the Lukad: An Online Journal of Pedagogy (Special Issue on Gender and Inclusive Education, April 2025).

Mr. Enaya critiques the way phenomenology, originally a philosophical method and then utilized by social science to investigate the lived experiences, is used in research on women.

Phenomenology tries to describe the “essence” of an experience by studying how people live through it. Applied to women, this means researchers often interview or analyze women’s narratives to describe what it means to be, for example, an “educated woman” or a “woman leader.”

At first glance, this sounds helpful. But Enaya warns that such studies often reduce women into fixed categories. By treating these experiences as universal, researchers unintentionally objectify women and turn them into objects of study instead of recognizing them as free individuals who define themselves. In simple terms, whenever scholars claim to describe the “essence” of a woman, they risk limiting her to something she did not choose.

The paper cites real-life contexts that show why this matters. In the Philippines, former President Rodrigo Duterte publicly said that the presidency was not for women, while also cracking jokes at women’s expense.

In academia, during the pandemic, studies found that men produced more publications than women, reflecting systemic barriers that women face.

These examples show that discrimination is still very much alive. When research methods unintentionally box women into categories, they can add to the problem instead of helping address it.

Instead of trying to define what a woman “is,” Enaya suggests a different approach, which is to start from the idea of the human person.

Women, like men, are free beings who create their own meaning in life. They cannot be reduced to universal formulas or fixed concepts. Focusing on women as free human persons avoids the trap of objectification and recognizes their ability to define who they are and who they want to become.

This perspective challenges both social science and gender studies to rethink how women are studied and represented. It argues that equality does not come from producing more definitions of “what a woman is,” but from recognizing that women, like all human beings, are not confined to predetermined roles. They are constantly becoming, making choices, and shaping their own existence.

For VSU, this work adds to the university’s growing voice in national and international discussions on gender and philosophy. It demonstrates how research from local institutions like VSU can question long-standing approaches in philosophy and social science, and propose alternatives that matter in everyday realities, from politics to education.

This research offers a reminder that while methods in philosophy and social science can open new perspectives, they must also be critically examined so they do not unintentionally contribute to the same inequalities they seek to address.

This article is aligned with the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 4: Quality Education; SDG 5: Gender Equality; SDG 10: Reduced Inequalities, and; SDG 16: Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions.